Recently, Indermit Gill, the chief economist and senior vice-president for development economics at the World Bank, wrote an article in the Financial Times titled “Nigeria’s economic transformation must succeed.” In the piece, he urged Nigerians to embrace the economic reforms of their president, Bola Tinubu. Specifically, Gill said: “The country’s elites must forge a political consensus in support of these reforms.”

That’s not surprising. Like every seasoned policy expert, Gill knows that without a political consensus, no reform, especially a radical one, can succeed. However, what he failed to say is why there is no political consensus in favour of Tinubu’s economic reforms. Yet, recognising and addressing that point is, in part, key to understanding why Tinubu is so unpopular, and why few embrace his “reforms.”

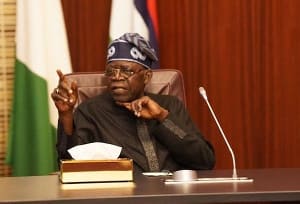

First of all, let’s be clear about this. Tinubu is the most unpopular civilian president in Nigeria’s political history to date. For a start, his somewhat miasmic past and the controversial manner in which he became president – namely, his divisive Muslim-Muslim ticket, his self-serving and ethnocentric ‘emi-lokan/Yoruba-lokan’ calculations and the deeply flawed election that brought him to power – gave Tinubu the hardest-ever landing for a president. No previous Nigerian president emerged under such untoward circumstances. Second, Tinubu’s utter unpreparedness for power beyond a self-entitled claim to it, evidenced by the incoherence of his policy agenda as well as his impulsive and rash approach to governance, has produced perverse consequences, making him and his administration even more unpopular.

However, one major factor that is rarely acknowledged in Nigeria is Tinubu’s shallow ‘mandate’ and the arrogant way he has ruled in spite of it. The Economist magazine and the Financial Times recognised long ago that Tinubu’s “weak mandate” could be an albatross on how he governed. But Nigerians hardly talk about Tinubu’s shallow ‘mandate’ and the constraint it places upon his ability to enact painful reforms. Yet, theory and empirical evidence tell us that the nature of a government’s mandate matters hugely.

In the book The Political Economy of Policy Reform, edited by the renowned economist John Williamson, several scholars studied successful economic reforms in many countries and distilled from those studies key principles about the conditions under which economic reforms could or could not succeed. Two of those hypotheses are relevant here: one is the crisis hypothesis; the other is the mandate hypothesis. So, what do the hypotheses say?

“But Nigerians hardly talk about Tinubu’s shallow ‘mandate’ and the constraint it places upon his ability to enact painful reforms. Yet, theory and empirical evidence tell us that the nature of a government’s mandate matters hugely.”

Well, according to the crisis hypothesis, only a major crisis can jolt a country out of sclerosis and trigger fundamental reforms. Thus, when a country faces a major crisis, tough reforms are easier to push through than when it faces no existential crisis. However, the mandate hypothesis says that there is greater scope for radical reforms if a government won a clear and strong electoral mandate for change than if it won a weak mandate. In other words, a party that put a radical reform agenda before the electorate and secured a strong support for it would have a greater leeway to implement the agenda in power than a party that received a weak electoral support for its agenda. This is because a government with a strong mandate is more likely to enjoy a honeymoon and face weak oppositions, both conducive for bold reforms, than a government with a weak mandate that may speedily run into troubled waters.

Now, let’s apply this theory to Nigeria. Everyone will agree that the crisis hypothesis favours Tinubu. He inherited a distorted and comatose economy, even though it was his party, APC, that crippled the economy in its eight years in power from 2015 to 2023. Yet, many analysts would concede that, as president, Tinubu should undertake far-reaching reforms to tackle the crisis. But the mandate hypothesis does not favour him. Tinubu won only 36.6 per cent of the popular vote, meaning that 63.4 per cent of the voters rejected him. Out of the 24m total votes cast in the presidential election, he received only 8.8m, meaning that a whopping 15.2m voters rejected him. Of course, he won the plurality of votes but that’s different from winning the majority of the total votes cast. That lack of popular mandate reinforces the political polarisation in Nigeria. Coupled with the poor handling of the weak mandate, it also explains why there’s no political consensus and popular support for Tinubu’s economic reforms.

Here’s a simple test. If you carried out an opinion poll across Nigeria today, you would find that most of those who voted for Tinubu in 2023 are making excuses for him. Even though they face economic hardship like most other Nigerians, they blame former President Buhari, not Tinubu, for it. But ask those who did not vote for Tinubu in 2023, most of them would blame him squarely for the current situation. Everything is viewed through a polarised political filter. That’s consistent with theory. According to the “choice supportive bias” heuristic in behavioural economics, people think positively about a choice once made even if it has flaws. Put simply, people don’t have buyer’s remorse easily unless something dramatic happens that forces them to change their minds.

But has anything dramatic happened to make most of the 15.2m Nigerians who did not vote for Tinubu in 2023 change their minds about him? Absolutely not. First, let’s be clear: the mandate Tinubu has is to govern with humility and consensus, not magisterially like an absolute monarch. Former Governor Kayode Fayemi famously said: “You can’t have 35 percent of the vote and take 100 percent. It won’t work.” But Tinubu governs arrogantly, taking far-reaching decisions unilaterally as if he won a landslide victory. Instead of seeking genuine cross-party consensus, he is using Nyesom Wike to cripple the PDP and other attack dogs to undermine the Labour Party. Yet, together, PDP, under Atiku Abubakar, and Labour Party, under Peter Obi, secured 13m votes or 54.5 per cent in last year’s presidential election. Those voters can’t be wished away!

Ideally, given the enormity of the challenges and the need to forge a political consensus for far-reaching reforms, Nigeria should have had a government of national unity. Unlike Tinubu who, in opposition, rejected the fuel subsidy withdrawal and condoned Buhari’s pegging of the naira, neither Atiku nor Obi opposed, in principle, withdrawing the fuel subsidy or removing the currency peg, although both said they would have done things differently. Thus, instead of being “possessed by courage” and blurting out subsidy is gone” and abruptly announcing other consequential economic policies on his first day in office, Tinubu should have forged a political consensus behind those reforms in thoughtful, impact-driven ways that would mitigate their adverse consequences and win public support for them.

Take South Africa. President Cyril Ramaphosa’s party, ANC, fell to 40 per cent in May’s election and had to form a unity government with the main opposition Democratic Alliance and other parties. Recently, he described the unity government as his country’s “second miracle”; the “first” being the one formed by Nelson Mandela after the collapse of apartheid in 1994. The truth is, difficult and far-reaching reforms are easier to pursue under a unity government as it is less difficult to forge a political consensus and build popular support behind them.

Yet, even without a unity government, Tinubu could still have mitigated his weak mandate by governing well, by assembling a first-class team. But he has not. His first cabinet was woeful, and the much-anticipated recent reshuffle” was a damp squib. Tinubu leads a minority government, yet his governing style is utterly arrogant. Little wonder political consensus and public support elude his “reforms”!

Stream, share and Read

CONNECT WITH NANTSAK NEWS